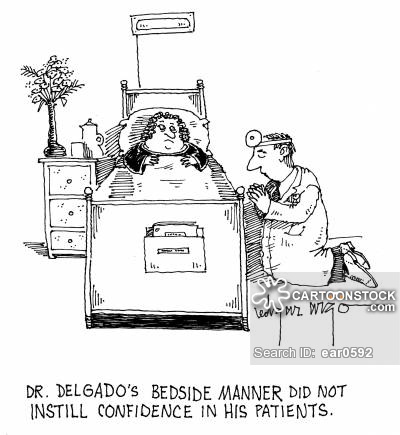

Dr. Delgado’s bedside manner did not instill confidence in his patients.’

During the 12 years of patient advocacy that I describe in my book, I repeatedly noticed that attending physicians did not “lay hands on” my parents very much in order to determine what was wrong with them or to assess their overall health status. Doctors of all levels of experience tended to rely heavily on laboratory tests and technology—imaging tests (CT scans, MRIs), for example, even when such technology was not indicated—and not on their own bedside clinical skills.

This was true whether my parents were in a hospital emergency department, a hospital intensive-care unit or other inpatient room, or a physician’s office.

Another observation: During their exams in both their primary-care physicians’ and specialists’ offices, the doctor’s laptop computer usually intruded as a third presence, potentially threatening the diagnostic process and the doctor-patient bond. One neurologist, whom I christened Dr. Less in “Our Parents in Crisis,” actually interrupted my father while he was explaining his symptoms and said to him: “Do you see this laptop? [indicating the computer permanently attached to her waist] You can’t talk faster than I can type into this laptop.”

Here was a doctor who thought her keyboarding was more important than listening to her patient’s concerns.

We live in an era of diagnosis-by-technology and “laptop doctors,” an era that has adversely altered the once-sacred doctor-patient relationship and the intimate ritual in which the participants formerly engaged. There actually are hospital ICUs in the United States where medical consultants conduct their “rounds” on patients via telemetry, communications that permit, for example, the adjustment of ventilator settings or drugs, remotely. These physicians are both physically and emotionally removed from patients, who are compelled to trust them without ever meeting them.

I believe in the time-tested history and physical (H&P) exam model—a doctor who listens attentively to what a patient says and does an appropriate physical exam—but I also appreciate the evidence that only technology can provide. A CT scan, or other vital image, can spell the difference between life and death—provided it is expeditiously ordered and properly interpreted. I agree with Dr. Abraham Verghese, Stanford professor for the theory and practice of medicine, that “clinicians who are skilled at the bedside [or in the office] examination make better use of diagnostic tests and order fewer unnecessary tests.”

While doing research for “Our Parents in Crisis,” I became acquainted with Dr. Verghese, a baby-boomer internist who has written extensively about the demise of the H&P and the deterioration in doctors’ bedside diagnostic skills. Much to the chagrin of internists from earlier generations, today’s internal-medicine trainees—future primary- and family-care physicians—can become certified by the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) on the basis of a multiple-choice test, never having to demonstrate hands-on patient skills.

The oral clinical examinations of the past, during which an outside examiner grilled a new doctor on what he/she learned in a bedside H&P of a real, live patient, and then often subjectively passed or flunked him/her, were discontinued in the mid-1970s, in part because of examiner bias. In my first book, “Starting With Serotonin,” I detail my father’s board-exam ordeal in 1958. After it was over, he trashed his internal-medicine textbook, which he had read in its entirety, “underlining every [bleep] thing,” in his New York City hotel room. The passage rate for orals then was only 50 percent.

One examiner actually queried my father on a new medical syndrome that he had defined and written extensively about. Dad felt certain that had he not openly acknowledged his own expertise, thus showing integrity, the examiner might have flunked him.

If he had, it would have been my father’s second failure. He believed he failed his first attempt at the orals because his examiner was a “son of a bitch from Washington” who knew him through a consultancy and had no love for the National Institutes of Health, where Dad worked. (“There was a lot of feeling against government medicine and government control then,” he told me. This was before NIH grants.) While my opinionated father would have been the first to excoriate the “ruthless” examiners, he and other post-World War II medical graduates, motivated in part by the board’s orals, developed excellent bedside skills.

“Without a high-stakes clinical examination looming over them,” writes Verghese, “the bedside skills of [today’s] trainees atophy. . . . [W]e certify internists in the U.S. without an external benchmark that ensures that they can find a spleen, elicit a tendon reflex, detect fluid in a joint, or detect a large pleural effusion by percussion. If the public fully understood this, [it] would be shocked.”

The ABIM’s all-day certification exam consists of multiple-choice questions with a “single best answer.”

The “good news,” Verghese says, is that internal-medicine house staff (interns and residents) and junior faculty members “are eager to improve” their bedside skills: They recognize the value of the clinical examination, especially in resource-poor settings, such as those found in Third-World and other countries. Whether this eagerness exists at many institutions outside of the elite Stanford is debatable. Judging from articles and books I’ve read, many physicians today believe the H&P is laughably prehistoric.

Verghese and his colleagues are not among them. To meet their trainees’ needs, they developed the “Stanford 25,” a list of 25 technique-dependent physical diagnostic maneuvers, which they teach them to perform in workshops with actual patients or patient-actors. I will list the techniques here and elaborate on some of them in my next blog posting.*

The 25 are:

1. Fundoscopic examination for papilledema (the eyes)

2. Examination of papillary responses (pupils)

3. Thyroid examination

4. Examination of neck veins/jugular venous distension (for cardiovascular problems)

5. Examination of the lung, including surface anatomy and percussion technique

6. Evaluation of point of maximal cardiac impulse and parasternal heave (for heart and lung problems)

7. Liver examination

8. Palpation and percussion of the spleen

9. Evaluation of common gait abnormalities

10. Elicitation of ankle reflexes, including in a recumbent patient

11. The ability to list, identify, and demonstrate stigmata of liver disease, from head to foot

12. The ability to list, identify, and demonstrate common physical findings in internal capsule stroke (the internal capsule is a common brain site for stroke)

13. Knee examination

14. Auscultation of second heart sounds, including splitting

15. Evaluation of involuntary movements, such as tremors

16. Evaluation of the hand for signs of disease

17. Inspection of the tongue for signs of disease, infection, etc.

18. Shoulder examination

19. Assessment of blood pressure

20. Assessment of cervical lymph nodes

21. Detection of ascites and abdominal venous flow (ascites is the buildup of free fluid in the abdomen, around organs)

22. Rectal examination

23. Evaluation of a scrotal mass

24. Cerebellar testing (cerebellum is critical in motor control and coordination)

25. Use of bedside ultrasonography

How many of the 25 techniques do you think your primary-care physician could perform effectively?

Ann, 5/2/16

*See special report about “The Stanford Medicine 25” and Dr. Verghese at http://sm.stanford.edu/archive/stanmed/2010summer/article3a.html; and Verghese’s article, “In Praise of the Physical Examination,” in “The British Medical Journal” (Dec. 2009) at http://www.bmj.com/content/339/bmj.b5448.